Indigenous Knowledge Systems reflect worldviews and ways to interpret the world that are based on incredibly technical methodologies and understandings. Our knowledge systems include deep insights into complex systems such as plants and trees (Kimmerer, 2018), fisheries (Reid et al., 2021), and sea ice (Dawson et al., 2020; Fox Gearheard et al., 2013; Krupnik et al., 2010; Laidler et al., 2008; Laidler and Ikummaq, 2008; Laidler and Elee, 2008). Our Peoples have always observed the environment and monitored conditions using key indicators (Ban et al., 2020; Kourantidou et al., 2020; Ban et al., 2018). This includes the knowledge and experience to provide leadership and rich contributions to documenting and understanding climate change impacts through direct knowledge and insights pertaining to weather, environment, wildlife and habitats, adaptation planning and modelling and through insights and wisdom related to alternate pathways and approaches to sustainable living (see Case Story 4; Case Story 5; Lim, Ɂehdzo Got’ı̨nę Gots’ę Nákedı [Sahtú Renewable Resources Board] and The Pembina Institute, 2014; Turner and Clifton 2009).

Although western science can describe the natural world, it does not speak to how to live with it (McGregor, 2018). Due to unique and holistic relations with the environment and an understanding of localized seasonal, cyclical and interdependent timing of events such as migrations, hibernations and blooming vegetation, Indigenous Knowledge Systems can identify changes undetected by western science (Chisholm Hatfield et al., 2018; Whyte, 2017a) and can provide more in-depth place-based understandings of changing environments over greater timescales than western scientific methods (Sawatzky et al., 2021; Sawatzky et al., 2020; Huntington, 2011; Gagnon and Berteaux, 2009).

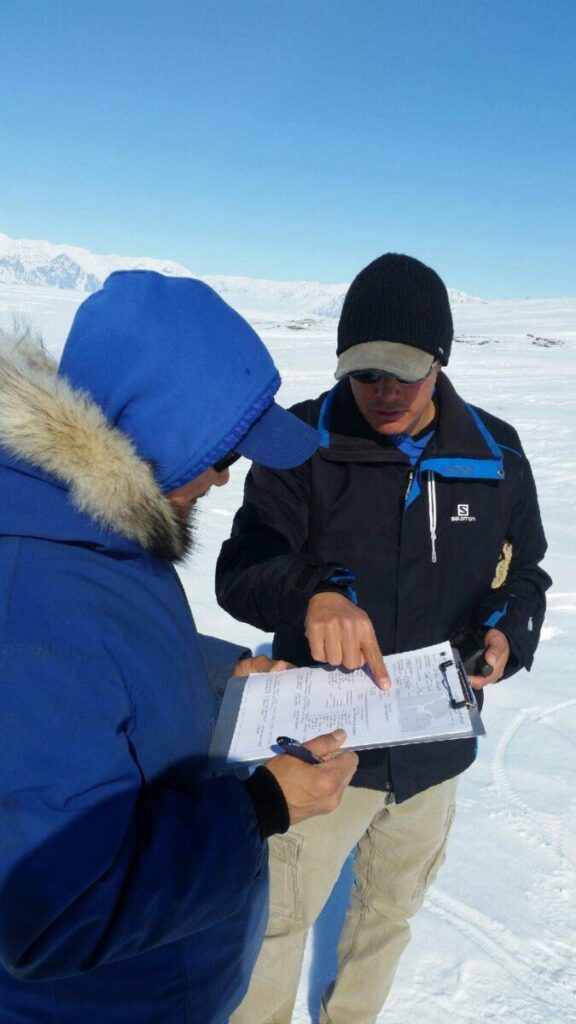

Approaches that braid Indigenous and western ways of knowing in environmental research and management have well-recognized benefits (Johnson et al., 2020; Alexander et al., 2019; Bartlett et al., 2012). Complex environmental issues like climate change can benefit substantially from multiple ways of knowing (see Case Story 6; Cuerrier et al., 2022; Tomaselli et al., 2022; Kimmerer, 2018; Alessa et al., 2016; Cuerrier et al., 2015). A co-produced or braided evidence-based approach supports complementarity of knowledge systems and values, while upholding the integrity of each system and without one being dominant over the other (Yua et al., 2022; Luby et al., 2021; Tengö et al., 2014). Etuaptmumk (Two-Eyed Seeing) is a concept described by Mi’kmaq Elder Albert Marshall as the process of bringing together multiple ways of knowing and a way of seeing from two eyes or lenses—an Indigenous eye or lens, encompassing Indigenous ways of knowing, and a western eye or lens, encompassing western ways of knowing (Bartlett et al., 2012). Indigenous Peoples worldwide have developed similar frameworks or practices of knowledge co-existence, including “Two Row Wampum” or Kaswentha in Haudenosaunee; “Two Ways” or Ganma in Yolngu; “Double‐Canoe” or Waka‐Taurua in Māori (Reid et al., 2021); co-production of knowledge by the Inuit Circumpolar Council; and the qaggiq model of Inuktut knowledge renewal based on late Inuk Elder Mariano Aupilaarjuk’s philosophical thinking (McGrath, 2018; McGrath, 2002). Through Two-Eyed Seeing and other practices for braiding multiple ways of knowing that support an ethic of knowledge co-existence, co-production, inclusive environmental co-research, monitoring, management and governance can be supported, and more holistic perspectives on socioeconomic, political and ecological changes are established (Harper et al., 2021; Reid et al., 2021; Dufour-Beauséjour and Plante Lévesque, 2020; Henri et al., 2020; Reed et al., 2020; Popp et al., 2019, 2020; Levac et al., 2018; Durkalec et al., 2015; Harper et al., 2012; McGregor, 2004).